By Kei Emmanuel Duku

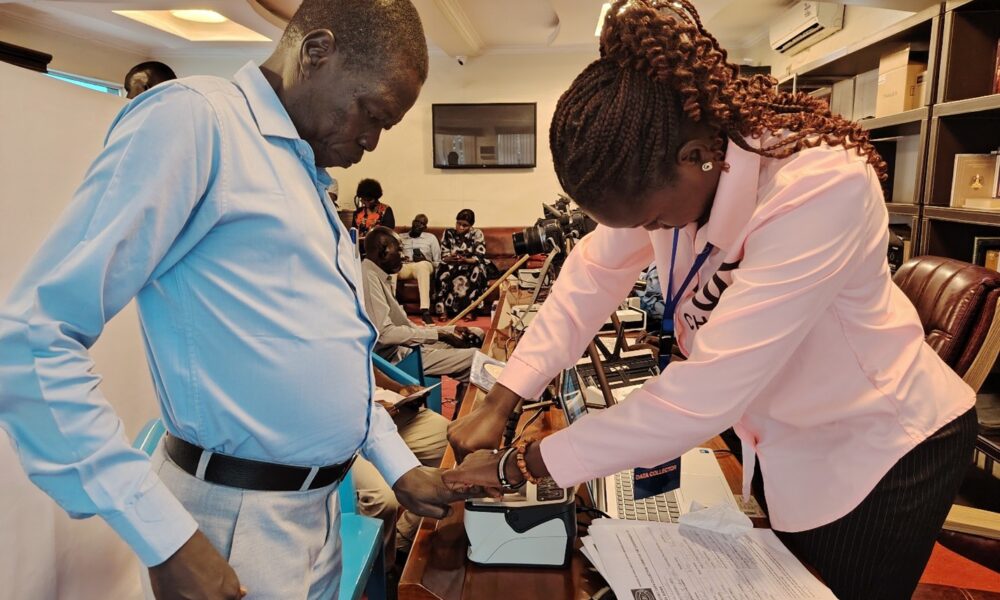

In the quiet corridors of Juba’s ministries, a digital revolution is unfolding one fingerprint at a time. For years, the Republic of South Sudan has wrestled with a “ghost” that haunts its national treasury: a payroll bloated by non-existent workers, duplicate names, and systemic inefficiencies. Armed with high-resolution cameras, thumbprint scanners, and a $15 million investment, the government is now attempting to eliminate these spirits to reclaim the national budget.

However, this is more than just a localized cleanup. Using biometrics to sanitize the payroll marks one of the first major steps South Sudan is taking to build a national Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI).

Building the ‘Digital Rails’

DPI is the modern equivalent of physical roads and bridges. It refers to a secure, interoperable network of digital components including identification, payment systems, and data exchange layers that allows a government to deliver essential services. When functioning correctly, DPI acts as the “digital rails” upon which a modern economy runs, ensuring different government systems can “talk” to one another to reduce corruption and improve service delivery.

For South Sudan, this biometric drive is a critical intervention in a landscape currently lacking of a well-established DPI ecosystem. The country currently lacks a national digital ID system at scale, possesses a fragmented digital architecture, and most critically has no comprehensive data protection law to serve as a safeguard.

In an economy heavily reliant on cash with limited ministerial interoperability, this $15M system is becoming, by default, the nation’s first major DPI building block.

Abraham Makur Mangok, the Director General of Human Resource Management, is the man tasked with leading this high-stakes headcount. For Mangok, the transition is about moving toward evidence-based administration.

“The essence of this biometric registration is for us to have data that we can use for planning and decision making,” Mangok explained. He admitted that since independence, the nation’s human resource management was never comprehensive, failing to capture the granular details of state servants. This project aims to bridge that gap, providing a data-driven bedrock for the national budget and a fair salary structure.

Although the current biometric information collected will be stored at the server of the Ministry of Finance and Planning, the questions regarding digital governance remains critical. For example without a formal data protection authority or established laws who ultimately controls this biometric data after the end of the project?, As the system rolls out in three phases first at the national level, then the states, and finally the organized force the government faces the challenge of building trust among a workforce wary of how their personal data will be secured.

The project is a collaborative effort between the Ministry of Public Service and Human Resource Development and the Ministry of Finance and Planning. Maxwell Melingasuk Loboka, Project Director for the Public Financial Management and Institutional Strengthening Project (PFMIS), noted that the current pilot is a litmus test for the system’s resilience.

Targeting five key entities including the Office of the President and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the pilot has already identified “digital divides.” Loboka pointed to internet connectivity and unstable electricity as primary threats to the rollout.

In the context of DPI, this highlights a major inclusion risk, for example in remote states with poor infrastructure, legitimate civil servants risk being excluded from the payroll simply because the “digital rails” cannot reach them.

Furthermore, experts warn that this system must eventually achieve interoperability. To move beyond being a “digital silo,” the payroll system will need to integrate with future National ID programs and passport enrollment systems to create a unified digital identity for citizens.

South Sudan is not alone in this journey. Minister of Public Service and Human Resource Development, Dak Duop Bichiok, noted that similar biometric frameworks have been successfully deployed in Somalia, Kenya, and Namibia.

The project is heavily cushioned by the World Bank, reflecting an Africa-wide trend where international financial institutions prioritize DPI in fragile states to stabilize fiscal management.

Charles Undeland, the World Bank’s Regional Director and Country Manager in South Sudan, emphasized that establishing an accurate count of public servants allows the government to manage budget outlays effectively.

Yet, regional lessons also sound a note of caution regarding sustainability. The system is being implemented by the Canadian-based firm FreeBalance. Critics of such rollouts often point to the risk of vendor lock-in, where a country becomes perpetually dependent on proprietary foreign technology rather than building local capacity.

A Path Toward Digital Trust

Despite the technical hurdles, the immediate administrative gains are evident. Stephen Pitia, Director for Human Resource Management at the Ministry of Presidential Affairs, noted that the system is already solving the “multi-identity” crisis.

“You will find an employee may have two to three names in a different institution,” Pitia said. “Even if you change the name, the fingerprint will indicate that you are the same person.”

At the Ministry of Cabinet Affairs, Site Supervisor Kur Deng Kuot reported that by early December, nearly 80% of the staff had been captured. The technology even accounts for physical difficulties; when thumbprints are hard to scan, high-resolution cameras utilize facial recognition as a secondary verification tool.

For veteran civil servants like Robert Belong Morbe, First Deputy Director of Cabinet Resolution in ICT, the shift from hard-copy files to digital databases is a long-overdue deterrent to corruption. The requirement for bank accounts to process salaries digitally is a major move toward creating the “payment rails” necessary for a functional DPI.

“When you have bank accounts, you bring your bank account to be included in the database so that your salary payment is processed digitally,” Morbe said, calling the move a commendable step toward transparency.

This sentiment is shared by staff like Asunta Jong Anel Chieny, a senior messenger in the Office of the President. She has seen colleagues who only appear when salaries are being paid. She welcomes the scanners as a “good decision” that rewards those who truly show up to serve.

As South Sudan moves forward, this $15M investment stands as a trial by fire. If the government can successfully navigate the complexities of data protection, system interoperability, and technical inclusion, this biometric drive will be remembered as the moment South Sudan began building its digital future.