By Kei Emmanuel Duku

South Sudan is facing a new environmental challenge, with experts pointing to the country’s vast livestock and traditional farming practices as significant contributors to carbon emissions.

This warning comes amid a global push to combat climate change, with the nation’s own agricultural activities now under scrutiny.

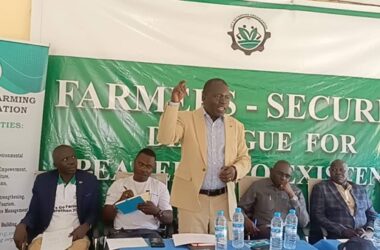

The issue stems from two primary sources cattle and land clearing for agriculture. Joseph Africano Bartel, South Sudan’s Undersecretary for Forestry and Environment, explained the science behind it. Cattle, he noted, are ruminants, which means their digestive process naturally produces methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. “When cattle eat grass… when they fart, what is coming out of them is methane,” he explained.

With an estimated population of 12 million cattle, 20 million sheep, and 25 million goats, according to a 2018 report from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the cumulative effect is substantial.

In agriculture, the problem is tied to deforestation. “When you are going to clear a lot of land, you are cutting a lot of trees that are contributing towards the sequestration of forest,” Bartel said.

Sequestration is the process where trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere. To combat this, he says, the world needs climate-smart agriculture, a system that seeks to produce food without increasing emissions.

Bartel highlighted that every human activity, from farming to flying, has a carbon footprint, or a total amount of greenhouse gases produced.

He explained that a potential solution lies in carbon trading, a system where countries that produce a lot of carbon can buy carbon credits from countries like South Sudan that naturally absorb carbon.

He clarified that this absorption happens through photosynthesis, a process where plants use sunlight and water to turn atmospheric carbon into organic matter.

This organic matter is essentially a form of stored carbon. “So our vegetation, our wetlands, our grasslands are there to absorb this atmospheric carbon in order to produce organic matter,” he said.

This process gives South Sudan a unique bargaining chip. “For develop countries to continue with that development path where they have to use or buy South Sudan carbon credits,” Bartel stated.

He added, “If they (Germany, United Kingdom, China, America, Brazil etc) are producing say one billion tons of carbon emissions and we are sequestering one billion, then we can now sell this credit of ours to them.”

However, he cautioned that South Sudan needs a proper framework and a stock take, or an official count, of its carbon absorption capacity to prevent exploitation. “We need to have a stock take to ascertain how much carbon our wetland, the largest in Africa, is sequestering,” Bartel emphasized.

The lack of a formal environmental law presents a major challenge to enforcement. Bartel clarified that while a draft act exists and has been handed over to the Ministry of Justice, it is not yet a law. But without the act, it doesn’t stop the country from trading with other nations adding that still South Sudan can use ministerial orders to make some decisions,” he said.

He said although, ministerial orders have their limitations. “It will be very difficult for the country to take sue violators to court… But now we are just doing it generally with the ministerial orders,” he said.

He further explained that the new act once passed, would create a powerful Environmental Protection Authority, a dedicated regulatory body with the authority to fine polluters, stop illegal activities, and enforce penalties.

South Sudan’s agricultural sector is fundamental to its economy and culture, with livestock ownership holding significant social and cultural value. However, the nation faces a complex challenge in balancing these traditional practices with the urgent need for environmental sustainability.

The country is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including floods and droughts, which directly threaten the livelihoods of its largely rural population. The shift toward sustainable practices and the potential for carbon trading represents a new economic opportunity for the nation, but it also highlights the need for a robust legal and institutional framework.

Furthermore, the current reliance on ministerial orders rather than formal law reflects the challenges of governance a nation still building its foundational institutions. This push for a new environmental act is a critical step in establishing the regulatory power needed to protect natural resources and capitalize on climate-related economic ventures.