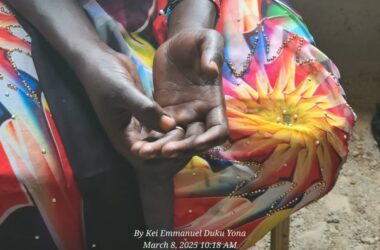

By Kei Emmanuel Duku

Abuu Sociva’s life story is a testament to survival, partnership, and the quiet war against stigma. Born with the HIV virus and orphaned by AIDS at a young age, Sociva, 30, has spent her entire life navigating the shadow of the epidemic a shadow she is now determined to lift for others.

Her story is one of profound health, domestic harmony, and a fierce commitment to dismantling the fear and discrimination that plague her community.

“I was born with the virus and I lived with it,” Abuu Sociva states, reflecting on a lifetime of challenges. She notes that despite having “been passing through them” for 30 years, she is healthy “thank God, through the medication.”

She attributes her normal, healthy existence not just to medicine, but to community support. She explains: “I’m living a normal life. And through support from other organizations who raised me up and provided me knowledge and experience. They have boosted me up so that I live a normal life.”

Despite her personal success, Sociva remains focused on the persistent cruelty of stigma. She warned that the core challenge remains “the issue of discrimination.”

When people realize an individual is HIV-positive, they face exclusion. Sociva reveals that families discriminate and “will not even give you access to education.” She describes a heartbreaking societal preference: “They may prefer those ones who are negative to go to school, to be safe and leave those ones who are HIV-positive. And they provide HIV negative children with love access to other social services.”

This segregation extends to daily life and even play. Sociva narrated that positive individuals may be given food separately and told not to eat with other children, lest they “affect those children who are HIV-positive.” The fear is so entrenched, she says, that “you find that they will not be even allowed to play with those kids who are health, if you or your children hold on their hands you or they are shouted at.”

The pain of discrimination is deeply personal for Sociva, who was orphaned early: “I am the only one remaining and my younger brother and both of my parents they passed away when I was young due to the AIDS and his brother was the one who took care me and I do not even enjoy the parental love.”

Sociva stressed that discrimination in South Sudan remains high, detailing common forms: “The common types includes physical, emotional, violence it may be by chasing or beating or denying other services at the home.”

Sociva’s own family life serves as a beacon of hope and mutual respect. “I’m married. I’m having three children with my husband. Those children, all of them, they are HIV-negative,” she specified. “One is 10 years, and another one is 8 years. Then the other one is still 2 years and a half. All of them are HIV-negative.”

The success lies in transparency and teamwork. She asserts: “And we live happily because we know our status and we adhere to treatment.” we adheres to treatment timing strictly, ensuring cooperation. She says: “If it’s time for medication I give to him, he takes, or we take all together. If he’s the one who gives to me, we always cooperate and take our medicine together.”

Their cooperation extends beyond health into a defiant equality in their marriage. She said in their entire marriage life “we have that equality whereby with my husband we do everything equal.” She explained that they switch roles freely: “When I’m cooking, he’ll be taking care of the kids. When I’m washing clothes, he’ll be the one who usually cook. We always cooperate together help him clean the house wash his clothes and bathe the child.”

She calls this teamwork a blessing: “That’s why I say that I’m so blesse, so people with HIV/ADIS should unite and cooperate and do everything together. There is nothing that this work is for a female or this work is for a man there is nothing in our marriage life or family.”

Yet, this equality is met with hostility. Abuu Sociva noted that “at the community level when the public see you as a couple doing all domestic work jointly they feel bad that you are using a charm or you have taken over of your man or maybe you have you have taken him to witchcraft.” This cultural opposition can turn familial, as “even the family members sometimes will not feel happy that because of the extent a man is doing household work. They will bring a lot of hatred between you and your husband.”

Sociva’s decision to disclose her status publicly was driven by a desire to save lives. “What came in my mind I saw people dying people who are having fear in their heart then I said that why can’t I help those who are like me by disclosing my status,” she said, so “they should know that I am HIV positive and later even after knowing their status they will be healthy and they will live the stress and be like me healthily and freely.”

She further added that her inspiration was driven by the person who helped her: “I took the decision to disclose because someone has made a decision like mine to rescue or serve me by disclosing and that person made me whom I am now if not because of that person I would not have lived this life today healthily.”

She sees public disclosure as the path forward. “That person had disclosed his/her status so when I saw that I have a long way to go to save lives through open disclosures and if every positive living do this we will have many long healthy people with meaningful life.”

Her 10-year-old son has noticed her medication, though she is waiting until he is older to disclose her status fully. She recalled him asking: “Mummy, every time these bottles are there, they cannot get finished. And every time, why are they there? I say I don’t know. Because those are medicine which I take. If I don’t take this medicine, I’ll not live for long. I’ll not take care of him. Then he feels like those medicines are very, very important to me. He did not even question me again.”

She however, warned about the precarious future of treatment dependent on foreign aid. “Without this medicine there is no life, for example South Sudan depend every day on donors like now the medication all this is being procured by donors and in future if this donors is leave, we the positive living don’t know what will happen.”

She urges the government to take control of the essential supply: “I really think with the government that we should have international or internal companies who can at least procure this medicine and support our people who are living with the virus.”

She concluded with a plea for self-awareness and testing: “Additionally the community have high level of stigma even testing they will not accept they may accept doing other tests but publically they will fear mostly. What I am suggesting in the community let them have self-type testing and know your health status because it is better to know your status at the earliest than just staying without knowing and at the end of when something happens you all know where you contracted it from before the stigma escalated.”