By Yiep Joseph

In the Greater Pibor Administrative Area, swollen rivers, vast wetlands, and long distances separate families from formal health facilities. Reaching children with lifesaving vaccines requires a system that can survive floods, protect supplies in harsh conditions, and deliver care far beyond clinic walls.

That system begins long before a vaccinator takes the first step. The Ministry of Health and UNICEF, through the Health Sector Transformation Project (HSTP), work together to safeguard every dose, from receiving vaccines, storing them safely, and keeping the cold chain intact even in one of the most remote parts of South Sudan.

Under the Ministry of Health–led HSTP, the Boma Health Initiative (BHI) is one of the key components. BHI is a government “homegrown” flagship strategy designed to strengthen and improve healthcare delivery, particularly in remote and hard-to-reach areas.

As the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) Manager for Greater Pibor, Joseph Lulclho oversees this delicate operation. “When we receive vaccines from the national government, we distribute them to our cold-chain stores. The Boma Health Workers pick them from there. It is not easy; I really appreciate them.”

With only a few functioning refrigerators across scattered facilities, the process must be precise. Temperatures are monitored closely, and vaccines are moved quickly to facilities equipped with UNICEF-supported fridges.

“Vaccines are taken to the facilities with fridges, and then we inform the community through chiefs and leaders. But vaccine protection does not end with storage. Families in Pibor move often between villages, seasonal settlements, and cattle camps, so the cold chain must travel with the people. If we find the family has moved, we follow them, sometimes even to the cattle camps,” Lulclho explains.

That careful preparation ensures that once the vaccines reach the hands of Boma Health Workers and vaccinators, they remain potent and ready to save lives. But the toughest work begins in the field.

At dawn each day, 24-year-old Samuel Agido slips quietly from his grass-thatched hut in Pibor town, leaving his wife and newborn child behind. By sunrise, he is already at Pibor Civil Hospital, picking up vaccines and preparing for another long day of walking for hours and wading through deep floodwaters to reach children who would otherwise miss lifesaving immunization.

“As health workers we move to villages; we walk for up to three hours to give vaccines to children and mothers,” Agido says. “It is now a passion for us, no longer a job for money, because sometimes our payment delays for long, but we continue. We want to help our people.”

During the rainy season, the plains turn into swamps and small streams swell into rivers too deep to cross on foot. But Agido refuses to turn back.

“I am short, and sometimes it is hard to cross where others manage,” he says with a smile. “So, I do swim until we reach together. I’m not worried, I am going to save lives, and God is always with me.”

Pibor Civil Hospital serves a catchment population of nearly 40,000 people, according to state health authorities. But for many families scattered across remote villages and cattle camps, the hospital remains far away, especially during the floods.

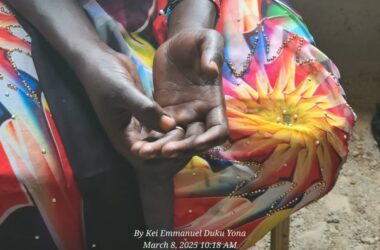

For mothers like 20-year-old Ngawun Kabacha, vaccinators like Samuel have changed that reality. He vaccinated her child directly in her village.

“My home is two hours on foot from the hospital,” she says. “But now my children get vaccines from the house. The health workers make life easier.”

Boma Health Workers Building Trust

In Longchout payam, Boma Health Worker Santino Allen starts his work long before he administers a vaccine.

“I encourage the mothers by giving health education, so they bring their children for vaccination,” he says. “I do not only vaccinate; I build trust. When a child is vaccinated for the first time, I visit the home and explain more about the vaccines.”

Convincing parents still requires patience. “Some mothers refuse at first, saying their children don’t need the vaccine,” Allen says. “It takes time to explain, but once they understand, they inform others.”

One of the mothers he supports, Ngawun Kabacha, six months pregnant, says Allen has helped her understand both vaccination and pregnancy and has vaccinated her children when she could not reach the health facility.

“I just imagine if the Boma Health Workers were not there how would I walk with two children and pregnancy for two hours?” she asks.

Local chief Sultan Korok Kusongun sees the work of Boma Health Workers every day. “Some areas are very hard to reach because of water, but our Boma Health Workers cross everything to give vaccines,” he says. “We coordinate with them, and I inform the community about the importance of vaccines.”

At the county level, the impact of HSTP is clear. Pibor County Health Director, John Thobok Awan, says the project is strengthening services and saving lives. “The project is bringing change. Our people are coming for vaccines. More lives have been saved”.

ForAfrika, UNICEF’s implementing partner in Pibor, plays a key role in supporting outreach across a population spread over vast and difficult terrain. County Health Coordinator Dr. Dolly Patrick says resilience is essential.

“Most of the population are in hard-to-reach areas, and they have no services. That’s why Boma Health Workers are key to reaching children.”

Dolly adds that HSTP’s focus on service delivery, capacity building, and incentives is strengthening the entire system. “Most health workers, including Boma Health Workers, are saving lives at the grassroots,” he says. “We are putting them at the forefront.”