By Alan Clement

In 2025, South Sudan’s political and social landscape was defined by a series of crises that tested institutions, disrupted daily life, and exposed persistent governance challenges.

From armed clashes in Upper Nile to judicial proceedings in Juba, from mass security operations to a devastating market fire, the year revealed the strain between state authority and public expectations.

The year began with violence in Nasir County, Upper Nile State, where clashes broke out between the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) and the White Army in March.

What started as a localized confrontation quickly escalated into a national political crisis. Government officials accused elements linked to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) of backing the White Army, while opposition figures denied responsibility. The confrontation led to significant political consequences.

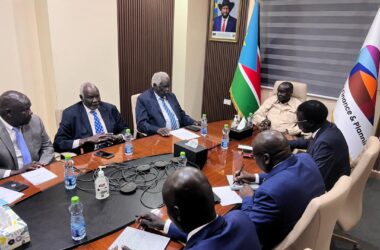

First Vice President Riek Machar Teny was arrested, suspended, and later charged alongside seven others, including former Petroleum Minister Puot Kang Chol. The charges ranged from treason to crimes against the state.

The decision to try the First Vice President under a special court marked a turning point in the country’s fragile political environment. The trial drew widespread attention and triggered extensive security measures in Juba.

Each court session in the Freedom Hall in Juba was accompanied by heavy security deployments, road closures, and traffic gridlock. These measures disrupted daily life across surrounding neighbourhoods.

Public servants arrived late to offices, traders reported losses, patients missed hospital appointments, and transport costs increased. For a city reliant on informal trade and daily movement, the repeated shutdowns translated into significant financial strain.

Activists raised questions about due process and judicial independence. Concerns were voiced about transparency and the selective application of justice. Parliament, however, remained largely absent from the process.

There were no sustained public hearings, no detailed reports assessing the legal basis of the special court, and no visible effort to address the socio-economic disruptions caused by the trial’s security footprint.

Mid-year, public anger surged following the gang-rape of a 16-year-old girl in Gumbo. The crime sparked widespread outrage, particularly among women’s rights activists and youth groups, who demanded stronger protection for vulnerable communities.

The government responded with a sweeping crackdown on street gangs, popularly referred to as “Niggas.” Security forces were deployed across Juba and other urban centers, leading to mass arrests of hundreds of young men.

Authorities described the campaign as a necessary response to rising gang violence. However, reports soon emerged that many detainees had no proven links to criminal activity.

Families struggled to trace relatives, legal representation was limited, and detention conditions remained unclear. Civil society organizations warned that collective punishment was replacing targeted law enforcement.

Allegations surfaced that some detainees were pressured into joining security forces, raising ethical and legal concerns. The crackdown created widespread fear. Young men avoided public spaces, not out of guilt, but out of fear of arbitrary arrest.

While the crackdown dominated headlines, underlying socio-economic drivers of gang activity remained largely unaddressed. Unemployment, urban poverty, lack of education, and absence of rehabilitation programs continued to fuel youth vulnerability.

The absence of coordinated social responses meant that the crackdown targeted symptoms rather than root causes.

Later in the year, a massive fire at the customs market destroyed goods worth millions. The blaze wiped out the livelihoods of traders who had invested savings, borrowed money, or pooled family resources to sustain their businesses.

Most affected traders were small-scale operators without insurance coverage. They formed a crucial backbone of state revenue through customs duties, local taxes, and daily fees.

The fire exposed weaknesses in South Sudan’s emergency response systems. Firefighters arrived late and under-equipped, with trucks repeatedly refilling from the river.

Coordination with Juba International Airport, which possesses modern firefighting equipment, was not evident. In the critical early moments, institutional fragmentation and unclear command structures delayed containment.

By the time additional resources were mobilized, the damage was irreversible.

Following the fire, traders awaited government support. No emergency relief package was announced, no compensation framework was established, and no temporary tax exemptions were introduced.

There was no public inquiry with findings shared transparently. Many traders were left stranded, forced into debt, or pushed permanently out of business.

The absence of official response reinforced perceptions that while the state collects revenue efficiently, it provides little protection or support when contributors face catastrophe.

Across these events; armed clashes, political trials, security crackdowns, and disaster response; a recurring theme was institutional weakness compounded by lack of accountability.

Agencies operated in silos, coordination was minimal, and mechanisms for public accountability were unclear. Parliament, constitutionally mandated to serve as a check on executive power, did not play a visible role.

It did not summon security chiefs to explain operational guidelines during the gang crackdown. It did not scrutinize the legal and political implications of trying a sitting First Vice President.

It did not launch inquiries into emergency preparedness after the customs fire. Its limited engagement allowed executive dominance to deepen and public frustration to grow.

The consequences of these developments were borne by ordinary citizens. Time lost in traffic translated into lost income at market stalls. Arbitrary arrests disrupted families and education. Fires destroyed livelihoods without safety nets.

Over time, these experiences eroded confidence not only in specific institutions but in the broader idea of the state as a guarantor of security and welfare.

By the close of 2025, South Sudanese citizens were asking fundamental questions. Was state power being exercised to protect citizens or to control them? Was justice being applied impartially or selectively? Why did taxpayers receive neither protection nor support in times of crisis? These questions reflected the broader uncertainty about accountability and governance.

The year highlighted several lessons. Security operations without accountability generated fear. Judicial processes without transparency undermined legitimacy. Revenue collection without social protection weakened the social contract.

Stabilization and progress would require Parliament to assert itself as an active oversight body. Emergency services would need integration and professionalization. Security operations would need clear legal standards that respect human rights.

In 2025, South Sudan was tested not only by armed groups and political rivals but also by its citizens’ expectations. The state’s responses marked by force, silence, and disorganization shaped public perception throughout the year.

Rebuilding trust will require institutions that listen, coordinate, and respond effectively. Without such changes, the disruptions and discontent that defined 2025 risk becoming recurring features of national life.