By Kei Emmanuel Duku

Twelve years after she was abducted during inter-communal violence in South Sudan’s Pibor area, a Murle woman has finally reunited with her family. But her return has triggered a dangerous dowry dispute between two rival clans, exposing the deep-rooted link between forced marriage, cattle raiding, and gender-based violence in one of the country’s most volatile regions.

The woman, whose name is being kept confidential for her safety, was only nine years old when armed men abducted her during a Sunday school service in 2012. The assault, part of a rise in violence between the Luo Nuer and Murle ethnic groups, left dozens of children kidnapped. According to her own account, at least 20 girls were taken that day. Only three, including her, have managed to escape over the past decade.

“I was just a child when they took me,” she said. “I didn’t understand what was happening. One minute we were singing in church, the next I was being dragged away.”

The 2012 attack was part of a broader pattern of inter-communal violence in Greater Pabior Administrative Area and the neighboring states that intensified after years of unresolved cattle raiding disputes, political tensions, and widespread availability of small arms. Armed youth groups have historically abducted women and children to claim compensation, secure wives, or initiate retaliatory raids.

According to researchers, such cycles of violence frequently recur during the dry season when communities move their cattle to grazing lands, increasing their vulnerability to raids and kidnappings.

Shortly after the abduction, she was handed over to a caretaker and forced into domestic servitude. She spent years cleaning, cooking, herding cattle, and fetching water. “They called it preparing me for marriage,” she said. “But it was slavery.” Days were long and grueling; she woke before dawn to collect water, clean livestock enclosures, and prepare food for her captors. She was not allowed to speak to other children freely and lived under constant watch.

Attempts to resist were met with beatings or starvation. Her sense of childhood faded quickly, replaced by fear and obedience.

As she grew older, she was “auctioned” to a man named Tudjua in exchange for 30 cows, a dowry that never reached her biological family. She was still in her mid-teens when she gave birth to her first child. She says her husband was a man as old as her father, a man she did not choose.

Escape and a Painful Choice

She made several attempts to flee, each ending in failure. During one escape, she was caught and imprisoned for two weeks. Her husband and his relatives then seized her two eldest children, threatening to kill her if she tried again.

“I knew I could die if they caught me a second time,” she said.

Her opportunity came unexpectedly during a wedding ceremony in Yuai village. With the help of a Murle elder who recognized her and alerted local chiefs, she slipped away while pregnant with her third child. This time, she did not look back.

The decision came at an unbearable cost: she left her other two children behind.

“Leaving them behind broke me,” she said. “But I believed God would one day reunite us, just like He reunited me with my parents.”

Dowry Dispute Rekindles Tensions

Her escape has reignited tensions between Tudjua’s family and the men who abducted her more than a decade ago. Tudjua’s relatives are demanding the return of the 30 cows they claim were paid as bride price. But the abductors divided the livestock years ago, and there is no clear way to reclaim or compensate for it.

“The two clans are now in conflict,” she said. “They are fighting over the cows. But I will never go back.”

Even after her escape, Tudjua’s relatives in Juba have continued to insist she is still his wife. They have made repeated demands for her return or for compensation, citing customary law. She has refused, saying she wants nothing to do with the forced marriage.

In many parts of South Sudan, cattle are more than property, they are the backbone of marriage, wealth, and identity. Bride prices can reach between 50 and 100 cows, which are amounts out of reach for most young men. This has fueled a system in which cattle raiding and abductions are not only common but also culturally tolerated in some communities.

“Dowry is at the heart of the violence,” said Kanan Gier Chol, former youth chairperson of Greater Pibor Administrative Area and now a head teacher in Juba. “Young men who can’t afford the high dowry raid neighboring communities or abduct girls.”

In these conflicts, young women and girls become commodities, exchanged, sold, and married off without consent. Abduction is often accompanied by sexual violence, forced labor, and social isolation. Survivors who return face stigma, psychological trauma, and economic marginalization.

Chol says the cycle can only be broken by reforming the dowry system and promoting reconciliation between communities. “If we bring down dowry to between 10 and 20 cows, and promote intermarriage between rival groups, we reduce the incentive for abduction,” he said.

A Mother’s Long Wait

For Naomi (not her real name), the survivor’s mother, the past 12 years have been defined by fear and heartbreak. She was abducted together with her daughter during the 2012 attack but was released after two days when the abductors argued over what to do with her. Her daughter remained in captivity.

“She cried every time I saw her during captivity,” Naomi said softly. “I will never forget those days.”

Every year, Naomi kept hoping for her daughter’s return. She would go to the church where the abduction happened, light a candle, and pray. “People told me to accept that she was gone,” she said. “But I refused.”

When her daughter finally returned in 2024, Naomi described the reunion as “a miracle”, but also “a new nightmare,” as the dowry dispute quickly escalated between the two clans. “Instead of celebrating, we are watching men argue about cows,” she said.

Experts and activists say stories like this are rarely reported. Abductions are often normalized, discussed only in soft tones, and resolved through traditional mediation rather than courts. In some cases, families accept dowry payments as compensation, effectively legalizing forced marriages.

“Survivors are silenced by shame and fear,” said a local women’s rights advocate in Juba. “They are told their marriages are legal, even when they were abducted as children.”

According to a 2024 report by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), inter-communal violence by armed groups accounted for nearly 79 percent of all civilian violence. Abductions of women and children were particularly prevalent in Jonglei State and the Greater Pibor Administrative Area, where decades of conflict, weak law enforcement and entrenched cultural practices have created fertile ground for such crimes.

A Weak Legal System

High Court Judge Sebit Bullen Lako says the justice system is struggling to respond. “Most areas have no forensic facilities, few investigators, and no gender desks,” he said. “That makes it difficult to bring perpetrators to justice.”

He added that many abduction and GBV cases are never reported, and those that are often collapse due to lack of evidence. “We need trained investigators, better infrastructure, and political will.” In many cases, survivors never even make it to court because they lack legal representation or cannot afford transportation to urban centers.

Some are discouraged by community members who warn them against ‘bringing shame’ on the clan. Others are silenced by threats from the abductors’ families. Legal aid organizations say the justice system remains inaccessible for most rural women, effectively denying them justice.

Under customary law, perpetrators can compensate for rape or abduction by paying cattle, effectively avoiding prison. For survivors, this often means being forced to stay in marriages they never chose.

Judge Faris, Hassan Odiel appointed First Grade Judge in Greater Pibor Administrative Area, says the region faces extremely high rates of child marriage, abduction, and GBV. But it has almost no legal infrastructure to address these crimes. “The area has no permanent judges, limited police, and no functioning criminal investigation department,” he said.

“We are drafting by-laws, but they are not yet operational,” he added. “Until then, abductors and rapists often go unpunished.”

Customary law plays a dominant role in rural South Sudan. Chiefs often mediate disputes involving abduction, dowry and marriage, sometimes without the involvement of formal courts. In some cases, chiefs order compensation in the form of cattle but allow abductors to keep the women they abducted, effectively legitimizing forced marriage.

The issue of abduction and forced marriage remains politically sensitive. In some counties, local administrators have attempted to launch reconciliation campaigns, but these are often undermined by the absence of sustained funding and political will.

Some local leaders have proposed creating specialized GBV courts and compensation funds to support survivors. But these efforts remain limited and underfunded.

Psychological Scars of Abduction That Don’t Fade

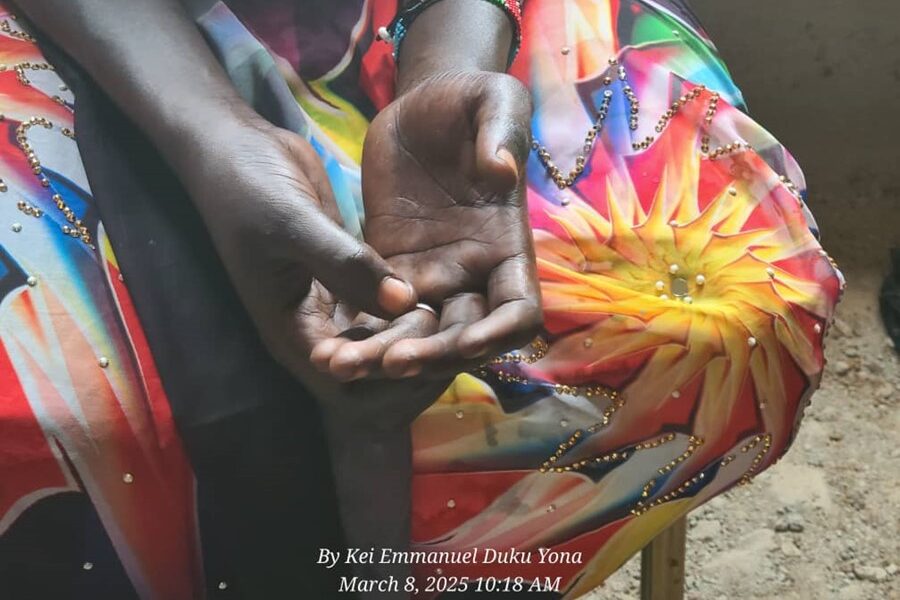

Twelve years of captivity have left deep emotional wounds. The survivor struggles with nightmares, flashbacks, and guilt over leaving her two children behind. She has no formal education and now relies on beadwork and small craft sales to survive in Juba. She also struggles with intense anxiety and an inability to trust strangers, often avoiding public gatherings.

Counsellors say this is common among formerly abducted women who have experienced years of abuse and coercion. Many women like her require long-term psychosocial support, which is scarce in most rural areas of South Sudan.

Trauma counsellors estimate that fewer than 15 percent of women returning from captivity receive structured mental health care.

“Sometimes I can’t eat,” she said. “I dream of the day I’ll bring my children home. God reunited me with my parents. Maybe He will do it again.”

The UN estimates that thousands of women and children have been abducted during inter-communal conflicts in Jonglei and Greater Pibor over the past two decades. Many remain missing. Others are living in forced marriages.

While South Sudan has ratified several international treaties on human rights and child protection, including the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, domestic legal frameworks remain weak. A draft Anti-Gender-Based Violence bill has stalled in Parliament for years. Meanwhile, customary law continues to dominate the justice system, often clashing with human rights principles.

The survivor’s case illustrates the difficult position many abducted women face when they return. On one hand, they are victims of crime; on the other, they are treated as subjects of clan negotiations. Their freedom often depends not on the law, but on whether clans can resolve dowry disputes.

For now, the survivor remains in hiding, fearful that her husband’s relatives may try to find her. But she has refused all pressure to return. “I have suffered enough,” she said. “This time, I choose my life.”

Her story is one of many, a single thread in a vast, tangled web of violence, culture, and impunity. The dowry dispute, like so many others, is not only about cattle. It is about who controls women’s bodies and futures in a system that has normalized their exploitation.

While for Naomi and her daughter, change cannot come fast enough. “I want my grandchildren home,” Naomi said, tears welling up. “I want my daughter to live free. And I want this to end, for every woman.”

International observers have long warned that abductions and forced marriages undermine South Sudan’s commitments under international law. The country is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), but implementation remains weak. Human rights groups say that without strong enforcement mechanisms and funding for protection programs, these international commitments remain largely symbolic.

Conclusion

The abduction of women and children in Jonglei and the Greater Pibor Administrative Area is not a new occurrence. Historians and conflict researchers have traced these practices back over many years, linking them to longstanding cycles of cattle raiding, ethnic rivalry, and weak central governance.

According to reports by Small Arms Survey and Human Rights Watch, the breakdown of traditional conflict-resolution mechanisms during South Sudan’s civil wars further undermined community trust, leading to armed youth groups that operate with a degree of independence.

Reports by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) document how, despite recurrent peace agreements and local dialogue initiatives, abduction remains a common tactic used to assert dominance, secure wives, or settle perceived inter-clan debts.

On paper, South Sudan’s Transitional Constitution and international treaties prohibit forced marriage and protect women and girls. However, legal experts interviewed for reports by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the United Nations Human Rights Council say that the lack of an operational Anti-Gender-Based Violence Act has left survivors relying on customary systems where chiefs hold significant authority. These customary forums often focus on compensation and clan stability rather than individual rights, a dynamic that weakens accountability for abductors and denies justice to survivors.

While customary law itself is not inherently abusive, as some legal scholars argue, it has often been exploited to uphold patriarchal control. In abduction cases, negotiations usually focus on cattle repayment or clan reconciliation rather than protecting survivors. Women are regarded as commodities rather than rights holders, and survivors are frequently pressured to return to their abductors or accept livestock as compensation.

International organizations, including UNMISS, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, have repeatedly urged the government to bridge the gap between customary and formal legal systems. Their recommendations include establishing specialized GBV courts, expanding legal aid for survivors, and creating prevention programs that target armed youth. However, progress has been slow.

Local authorities often cite limited resources, political sensitivities, and ongoing insecurity as obstacles to reform. Meanwhile, communities remain trapped between a weak legal system and traditional structures that frequently perpetuate harm.

Analysts and rights monitors warn that without structural change, the next generation of girls will face the same risks. As this survivor’s story shows, abduction is not just an individual tragedy; it reflects a broader system that has normalized violence against women and girls. They argue that ending it will require political will, legal reform, community engagement, and sustained investment in peacebuilding.